Full Interview

My name is John Finn and I live with my family in Ithaca, New York. Ithaca is where I grew up as the son of Bob Finn, a Professor of Chemical Engineering at Cornell University. Biochemical Engineering and Microbiology were his fields so I grew up with the lab work of applied microbiology and wastewater treatment. That’s what we talked about a lot and what I did even as a teenager so I got an early start in applied microbiology and engineering and that led me to getting degrees in Chemical Engineering at the University of Connecticut and then a Master of Bioengineering at Cornell back home.

With that I went on to start my career in engineering with several firms that were doing remediation of contaminated sites across the U.S. With that career I lived in Boston, Seattle, and finally Ithaca. That’s what I did for a majority of my career: cleanup of hazardous sites on a project-by-project basis with a team of interdisciplinary geologists, scientists, and engineers for attorneys, regulatory agencies, clients who were responsible for those properties and their cleanup. That was really the thrust of my engineering career, very multidisciplinary, working as a consultant doing a lot of different things all in that area.

In the middle of that career, after about 10 years, my wife and l with our little daughter went to Cambodia. We just unplugged from our regular careers. For 2 years we did voluntary service with a world development and relief organization in Cambodia called the Men In Night, a church-based organization. At that point, Cambodia was still very much recovering from the Cambodia genocide and the Khmer Rouge were still very active. There was a curfew at night and restrictions on where we could go. There was a very heavy presence of mines, so we had to be very careful of where we walked out in the rural areas. All that was an intense experience but I was inspired by the Cambodian's that I worked with there, that I am still in touch with, as they rebuilt their country. It was a very inspiring time; I learned a lot from them.

That's really my background. I have a broad engineering knowledge, love working with interdisciplinary teams, and my worldview is shaped by my experience in Cambodia. I am now in Ithaca raising my family. I am no longer doing day to day engineering consulting. I retired from that. Now for the past five years I've been focusing on climate change, education advocacy, AguaClara work and habitat protection with my daughter.

How did you become involved with AguaClara Reach?

So this is a fun story. Many things have to do with friendships right? In 1995 I returned with my family to my hometown of Ithaca and soon after I returned I connected with other people who had done similar kinds of overseas service work including Monroe [Weber-Shirk]. We are a part of a group that met weekly and have continued to do so. So back in 95-96 we became friends, our daughters were the same age, and they became young friends.

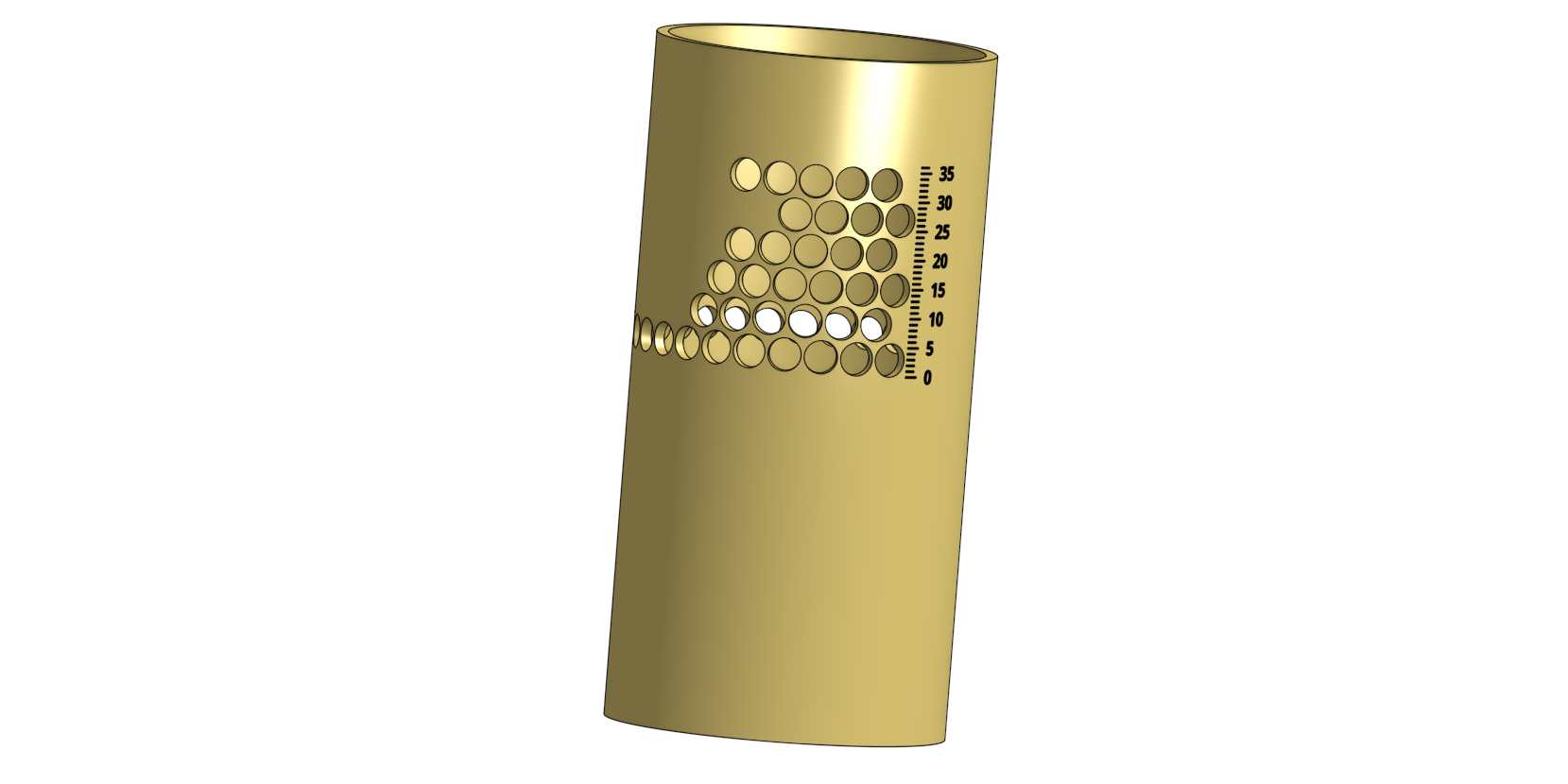

Since 1995 I have been meeting and talking with Monroe once a week - socially just as friends. Through that I followed what has happened with Monroe’s research and teaching at Cornell. Monroe’s work was developing into this new avenue of what he would describe as “finding that edge of knowledge.” Essentially, finding those places where the knowledge of water treatment needed sharpening. I was following the progress that Monroe and AguaClara Cornell, his team of student researchers, were making. I really became involved more in 2012-2013. That was when three of Monroe’s former students had graduated and wanted to form a company that would take AguaClara technology and expand it through the world. That company was called AguaClara LLC and May Shariff was one of the founders. AguaClara LLC was looking for advisors and I was happy to join their team.

So May and I started our friendship. I was advising AguaClara LLC from time to time back in 2012. Through the evolution of the LLC into the final change to a non-profit, May asked me to be one of the primary people who would lead that effort. That was the summer of 2017. That’s when I started putting in more time and more hours as we created the non-profit. All together I’ve been working with AguaClara for nine years.

What have your roles been at ACR and what did that day-to-day work look like?

I was the president of the AguaClara Reach (ACR) Board of Directors starting in 2017 through July 2019. From 2019 to this summer I continued as a Board of Director and starting this summer I started serving as a technical advisor to the ACR Board.

What I do right now is more hands off work with contacts that I’ve made and using my insights to be helpful to the organization. One of the main things is that I am not an AguaClara specialist, although I am an engineer and I am a generalist. I've followed it enough to get most of the technology, I understand it, but I couldn't design it myself. However, I am able to communicate it to others who are outside of AguaClara. I see it as one of the primary aspects of my role especially with potential donors or advisors to the organization.

So I've been in touch with people who've been involved with professional development, people who I've known since my days in Cambodia with a lot of experience in advising, people who would see an opportunity to be involved in financial support of the organization, and people who have a heart for the work and mission of the organization. I connect them with ACR and help explain what we do and what we aspire to do.

What strengths do you bring to ACR?

I am one of those people who enjoy talking with strangers or those who are just acquaintances, viewing them as future friends. So that’s one of the things: I can speak very well. Also I really enjoy understanding where people are coming from, what motivates them, why they might be interested in some part of AguaClara Reach. I am able to connect personally with partners, donors, advisors, volunteers, and employees.

I also have been involved with business and consulting for decades so have experience in some areas around personnel issues, hiring, and contracts. I can fill in as a consultant working with clients by putting myself in their shoes and know how to engage with them in ways that will lead to win-win situations. Although I’m not a contract specialist I have written and helped teams write competitive proposals for decades; I can help with proposals, prices and so forth. So that gives some of the unique things that I bring to the organization.

What is your favorite or most memorable moment with ACR?

It’s hard to pick just one but one of my favorites is definitely the moment when we were celebrating because we had achieved a pretty big milestone. Blixy [Taetzsch], May, Monroe, and I among others were working quite hard during the first year of ACR to get the federal designation of 501(c). That rolls off the tongue, “We are a non-profit. We are a 501(c) organization.” It seems like a simple thing, but it was not at all a simple thing. It was a lot of hoops to jump through and it was uncertain when we would be approved for that. The federal government needs to do that and there’s a long queue and a review process. Oftentimes it gets kicked back and you have to wait for another year. That did not happen with us. We worked really hard at providing applications that were thorough, understandable, complete, and met the criteria to be a non-profit as a New York State corporation and most importantly a 501(c)(3) with tax advantage status. That is not a small thing. It was a pretty big event that we were able to celebrate in early 2018 when we got the news on that.

I would say another thing that was just as amazing and really wonderful was in July 2019 when Alissa [Diminich], Zoe [Maisel], and Serena [Takada] really stepped up and said yes we will be a part of ACR. Alissa said “I am willing, able and enthusiastic about taking up the president role in the organization” and that fresh energy was just a life saver in that part of 2019. There were a lot of difficulties, and I had a very tough time during that year. That was just such a huge water shed when Alissa, Zoe, Serena and others got involved. To say that, “We are going to do this. We are going to rally and pull together. We are going to reform our organization and put fresh energy in.” And they really did and that was a huge high point for me as well.

Why is providing people with access to safe water so important to you?

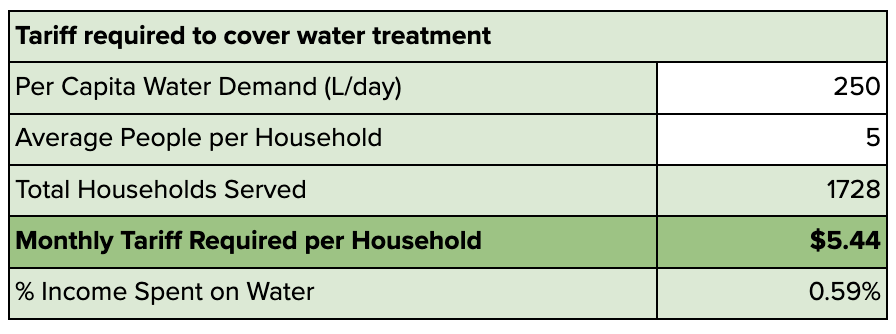

There’s nothing like having lived among folks for whom they don’t take water for granted. I have always lived in Ithaca. I grew up here. Traveled around and lived in other places in the U.S. At no point did I wonder if I was going to have water or safe water ever. When I lived among folks in Cambodia for whom that was an open question. Where they were going to get water and how much it was going to cost. How much of a percentage of their income was it going to take for their family to have water. That was a new experience. I had read about it, known about it, and seen movies about it but actually living and seeing that and the creative responses that people in that situation have been eye opening. My experience in Cambodia inspired me and lead me to have enthusiasm for the work of AguaClara Reach and the potential of AguaClara Technology to close the gap in access to safe water.

What influencing factors have driven your career and life choices?

One thing that really influenced my life was being around international students growing up. My father brought home grad students to dinner very often. It was an atmosphere where friendships were as important as the scholarship that he was involved in as a professor. Students from all over the world expanded my world view and encouraged me to try and understand where people are coming from.

In terms of my career, I wanted work that was worthwhile. Making the world better in even a small way was fulfilling. Doing that with likeminded people was a joy. Solving problems, finding better solutions, and fixing things with people in a team effort was sometimes more fun than fun. It was work but it was definitely fun. That’s been something that has continued to motivate me in engineering and in life. These are some of the reasons I find joy working with ACR.

How do you spend your free time?

I have a great amount of hobbies. I call myself a dabbler. I am not somebody who totally masters one thing very well. I just enjoy a lot of variety. For example, for the past 20 years I have been playing guitar. At first I could only play three chords but with a little bit more time, with the help of YouTube, and with the help of some friends, I am now an intermediate guitarist. I play the guitar a lot. I like acoustic, pop, and various blue genres with American roots.

I make wine at home and hard cider. My father made wine for many years, and I learned from him. For the past 25 years, I’ve been making my own wine and for the past 10 years, I’ve been doing that more and more. Now I am a part of a home winemakers club. We taste each other’s wines. Every fall I get juice from a winery that sells just the juice and select yeast. Then I ferment the wine and bottle it myself and have it with friends and family.

I enjoy the outdoors so I’ve been doing more lake and river kayaking. I’ve started birding for the past few years.

Is there anything else you would like to see within the ACR community that you would like us to accomplish?

I’m excited and enthusiastic about this next phase of the organization. It's great to be a part of something that is growing and expanding, and I see that continuing.

I see a handful of people doing a lot of the heavy lifting and I’ve been there too. I think at this stage it’s important to take care of ourselves and I think we’re good at doing that. I’d like to see the organization continue to take care of ourselves as we engage with others towards their health. I see the many opportunities that we have: everything from working with new partners to engaging more deeply with partners that we had before. It is important that we value and nurture our existing relationships and partnerships but it is also important to engage more with other nonprofits, experts, partners, and donors. I would like to see us reach out to some of those organizations and people.

It frustrates me when I see organizations almost compete as if it’s a zero-sum game meaning headlines or donors. ACR, on the other hand, is a collaborative organization and there are others who share that mindset of collaboration. Creating win-win mutually beneficial partnerships will be helpful to expanding the work and the mission of AguaClara Reach.

Do you have any last comments?

It’s been a really great run! Never a dull moment and I wish everybody well. Especially volunteers like yourself; thank you for your enthusiasm and continued commitment to the work or the organization! I’m looking forward to seeing how this next phase develops and unfolds.

I’m glad to still be a part of it.